In this post I’ll discuss how alignments work in SwiftUI, building our understanding of how they function, and finishing by demonstrating how to create your own custom alignments for specific needs.

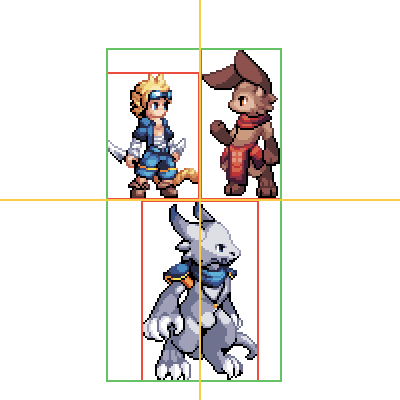

Let’s start by taking a simple view that lays out horizontally three images of different heights:

struct ContentView : View {

var body: some View {

HStack(alignment: .top) {

Image("rogue")

Image("dragoon")

Image("brawler")

}

}

}

After reading about stacks you’ll expect that each of the three Image

child views will be laid out horizontally from the HStack’s leading to

trailing edge, with some spacing between them.

You’d know that the size of the HStack is the union of the bounds of

its children, and that this means that its width is the sum of those

plus spacing, and its height is that of its tallest child.

It was also explained that the alignment of each child can change the positioning and height of the stack, and that’s what we’ll look at now.

We’ll look at horizontal stacks first, and skip over vertical stacks since they function the same way just in a different axis, and then we’ll cover the z-axis stack.

Alignment Basics

Alignment positions views only in the perpendicular axis of the stack: vertical alignment for a horizontal stack, and horizontal alignment for a vertical stack.

A common error is to seek to use alignment to change the position of a child view in the same axis as the stack.

If we’ve understood the behavior of the stack, we’ll realize that the horizontal position of a child in a horizontal stack is simply determined by the widths of the previous children in that same stack, plus spacing.

Since views choose

their own sizes we don’t

need alignment at all for that; we simply ensure the preceding views

choose widths that we want, or wrap them in .frames that choose the

desired width.

In our example it’s the vertical positioning of views laid out

horizontally that we care about. We’ve used the .top alignment in the

example, and as expected this aligns all of the views to the top of of

the stack:

To our usual red borders for the images, we’ve used a green border for the stack, and added a yellow line to indicate the common point of alignment for the views.

We know what we expected the result to be, and hopefully it’s not a surprise, but it’s worth stepping through the process of alignment with this simple example before we take on something more complex.

An alignment is a key to a set of values that a view can return,

called alignment guides. Each of these guides is simply a value of

length in the view’s own co-ordinate space, from its top-left corner.

The default value of the .top alignment guide for a view is simply 0.

The process of alignment within the stack is to convert those values from the child view’s co-ordinate space, into the stack’s, vertically repositioning either the new child or the stack’s existing children so that the position of the same alignment guide across all of its children views match.

The stack considers each child in turn, comparing the relevant alignment guide of the new child with its own value, which begins as 0.

If the new child’s alignment guide value is greater, the vertical position of all existing children in the stack is increased by the difference, and the stack’s value of the alignment is updated to be equal to the new child’s alignment guide.

If the new child’s alignment guide value is lesser, the vertical position of the new child is set to the difference, and the stack’s value of the alignment remains the same.

Since the stack’s alignment value begins as 0, and in the case of .top

each child’s alignment guide value is 0, the different is always 0 so no

vertical repositioning occurs. The stack’s alignment remains at 0, and

each child’s resulting vertical position is 0.

Center Alignment

Since .top was the easy case as no vertical repositioning was

necessary, now let’s instead consider the apparently more complex case

of .center.

The code is fundamentally the same, all we change is the value of the

alignment parameter to HStack:

struct ContentView : View {

var body: some View {

HStack(alignment: .center) {

Image("rogue")

Image("dragoon")

Image("brawler")

}

}

}

It’s helpful at this point to have a reference to the values of the alignment guides for each of the images we’re using.

| Image | .top |

.bottom |

.center |

|---|---|---|---|

| rogue | 0 | 64 | 32 |

| dragoon | 0 | 91 | 45 |

| brawler | 0 | 76 | 38 |

By default, the .top alignment guide is always 0 and the value of the

.bottom alignment guide is simply the height of the view, since that’s

the length in the view’s own co-ordinate space from the top edge to the

bottom.

The value of the .center alignment guide is derived from these two,

and is the distance from the top to the position halfway between its

.top and .bottom alignment guide. This is done automatically for us,

but the code inside SwiftUI to do that is simple and worth a pause to

consider:

// The complicated, but correct, definition.

d[.center] = d[.top] + (d[.bottom] - d[.top]) / 2

// If we assume .top is always zero.

d[.center] = d[.bottom] / 2

We don’t need to define this alignment ourselves, so let’s go back to

our example above and see what happens when we use .center alignment:

Now that we’ve walked through the alignment process for .top, and seen

the values of the alignment guides for .center, we can follow the same

process and reason about what’s going on.

The stack begins an alignment value of 0 and considers each child in turn.

The rogue Image is the first child, with a value of 32 for its

.center alignment guide. Since this is greater than the stack’s

current value of 0, and there are no existing children to reposition,

the Image is positioned at 0 and the stack’s alignment guide value set

to 32.

The dragoon Image is the second child, with a value of 45 for its

.center alignment guide. Since this too is greater than the stack’s

current value of 32, the existing children are repositioned by the

difference, in this case 13. The new Image is positioned at 0 and the

stack’s alignment guide set to 45.

The brawler Image is the third and final child, with a value of 38 for

its .center alignment guide. This is less than the stack’s current

value of 45, so the new Image is positioned vertically by the

difference of 7, and the stack’s alignment guide left unchanged.

So as we can see, despite being a more complicated result, the process

of .center alignment is identical to that of .top alignment, just

with different values for the relevant alignment guide.

Custom Alignments

Let’s take this further and see what it takes to create a completely custom alignment. Remember that an alignment only affects the position along the perpendicular axis of the stack.

For our example, we want to align our characters so that they appear to

be standing on the same plane. We could try using the .bottom

alignment but due to the differences in drawings, that doesn’t quite cut

it.

This is an ideal situation for creating and using a custom alignment.

First let’s remember that an alignment isn’t anything special, it’s just a key to a set of values associated with a view. To create a custom alignment, we need to define a new key, and to use a custom alignment we need to provide a value for that key for views we wish to align with it.

Keys for vertical alignments, such as we use for a horizontal stack, are

instances of the VerticalAlignment type. The .top, .center, and

.bottom alignments we’ve used so far are static properties of the type

that return an appropriate instance.

To define our own we add our own static property that returns an

instance for our new alignment. To create the instance we need a type

that confirms to the AlignmentID protocol, this acts as the identifier

for the alignment, and provides a default value for the alignment guide

of any view that doesn’t otherwise specify it.

Since we want to align our images based on their feet, we’ll call our

new alignment .feet. As a default value the existing .bottom

alignment works well enough.

extension VerticalAlignment {

enum Feet: AlignmentID {

static func defaultValue(in d: ViewDimensions) -> CGFloat { d[.bottom] }

}

static let feet = VerticalAlignment(Feet.self)

}

We can now use .feet anywhere we would have used .bottom and it’ll

have the same effect.

That’s not quite enough, we now need to use this alignment by changing

the values of the .feet alignment guides for our images. Remember that

these values are simply lengths, in the image’s own co-ordinate space,

from its top-left corner; we don’t need anything complicated here, we

can directly use the vertical pixel positions that we measured in

Photoshop.

struct ContentView : View {

var body: some View {

HStack(alignment: .feet) {

Image("rogue")

.alignmentGuide(.feet) { _ in 61 }

Image("dragoon")

.alignmentGuide(.feet) { _ in 84 }

Image("brawler")

.alignmentGuide(.feet) { _ in 70 }

}

}

}

Compared to our previous examples, in this example we set alignment

parameter on HStack to our custom .feet alignment, and for each of

our images we added an .alignmentGuide(.feet) that returns a value for

that alignment guide.

No new magic is required to perform this layout. As the stack considers each of children, as before, it simply reads the alignment guide values we’ve provided to determine how to vertically position each child.

For the second Image with a value of 84, this is greater than the

stack’s alignment value of 61 (obtained from the first Image), so the

existing children are repositioned by the difference of 23.

For the third Image with a value of 70, this is less than the stack’s

alignment value of 84 (updated by the second Image), so this child is

positioned at the difference of 14.

Aside from the different values, this is the exact same process used for

the .top and .center alignments we’ve seen so far.

Derived custom alignments

For our example the hardcoded pixel positions were sufficient, but the

.alignmentGuide modifier closure receives a value of the

ViewDimensions type.

We can use this to derive complicated alignment values in the same way

that SwiftUI derives the value for .center from the .top and

.bottom alignment guide.

The closure accepts a dictionary of the current set of alignment values, for this example we didn’t need that, but we can use that to make any combination of alignments we desire.

For example an alignment guide that is 75% of the height of the view:

Image("cleric")

.alignmentGuide(.custom) { d in d[.bottom] * 0.75 }

Or a vertical alignment guide that is the derived from the width of the view:

Image("wizard")

.alignmentGuide(.square) { d in min(d.width, d.height) }

Keep in mind that while powerful, you’re still limited to only affecting the vertical position within a horizontal stack, and the horizontal position within a vertical stack.

Expanding a stack with custom alignments

So far our examples haven’t caused the tallest element to be repositioned, this was deliberate to allow the fundamentals of alignment to be understood, but it is possible.

As we know, when a new child is considered with a value for the alignment guide that is less than the stack’s value, the new child is vertically positioned by the difference.

We’ve only considered alignment guide values within the bounds of the tallest image, what if the values are out of those bounds, or cause the tallest image to need to be vertically positioned?

Since the size of the stack is the union of the bounds of its children, this includes any vertical repositioning, and thus the stack is expanded in height to accommodate them.

Let’s demonstrate with some code that uses a custom alignment to align the three images in such a way that the tallest image needs to be vertically positioned:

extension VerticalAlignment {

enum Custom: AlignmentID {

static func defaultValue(in d: ViewDimensions) -> CGFloat { d[VerticalAlignment.center] }

}

static let custom = VerticalAlignment(Custom.self)

}

struct ContentView : View {

var body: some View {

HStack(alignment: .custom) {

Image("rogue")

.alignmentGuide(.custom) { d in d[.bottom] }

Image("dragoon")

.alignmentGuide(.custom) { d in d[.top] }

Image("brawler")

.alignmentGuide(.custom) { d in d[.center] }

}

}

}

The intent is that the bottom of the rogue is aligned with the top of the dragoon and the center of the brawler, and that’s what we get:

This alignment meant that the horizontal stack had to be expanded vertically to accommodate the vertical position of the dragoon image, and as we can see from the green border, it was.

Let’s go back over the process once more to see that the process is the same:

The stack begins with an alignment value of zero and considers each child.

The rogue Image is the first child, with a .custom alignment guide

value of 64. This is greater than the stack’s current value of 0, and

there are no existing children to reposition. The child is positioned at

0 and the stack’s alignment value set to 64.

The dragoon image is the second child, with a .custom alignment guide

value of the image’s .top, which is 0. This is less than the stack’s

current value of 64, so it’s this child that is positioned vertically by

the difference of 64. The vertical position of the existing child, and

the stack’s alignment value, both remain unchanged.

The brawler image is the third and final child, with a .custom

alignment guide value of the image’s .center, which is 38. This too is

less than the stack’s current value of 64, so it’s this child that is

positioned vertically by the difference of 26. The vertical position of

the existing children, and the stack’s alignment value, both remain

unchanged.

ZStack Alignment

This post has concentrated on alignment within a horizontal stack to demonstrate the fundamentals. Transitioning the concepts to a vertical stack simply replaces the vertical positioning of the horizontal stack to a horizontal position within the vertical stack. But what about the z-axis stack?

The size of a ZStack is still the union of the bounds of its children,

just that its children are overlaid over each other and we have

flexibility in both their horizontal and vertical positioning.

Since we know we can also expand the vertical size of a horizontal stack through vertical alignment, it should come as no surprise that we can expand the size of the z-axis stack through alignment in both axes.

For alignment a ZStack accepts an instance of an Alignment type,

which is initialized with instances of HorizontalAlignment and

VerticalAlignment for each axis.

We can build on our knowledge of custom alignments to define our own

.anchor alignments that we’ll use to layout our views:

extension HorizontalAlignment {

enum Anchor: AlignmentID {

static func defaultValue(in d: ViewDimensions) -> CGFloat { d[HorizontalAlignment.center] }

}

static let anchor = HorizontalAlignment(Anchor.self)

}

extension VerticalAlignment {

enum Anchor: AlignmentID {

static func defaultValue(in d: ViewDimensions) -> CGFloat { d[VerticalAlignment.center] }

}

static let anchor = VerticalAlignment(Anchor.self)

}

extension Alignment {

static let anchor = Alignment(horizontal: .anchor, vertical: .anchor)

}

These default to the center, but allow us to move the anchor of any one

of our views, in either dimension. So let’s take advantage of this by

making a ZStack of our views with the rogue and brawler above the

dragoon:

struct ContentView : View {

var body: some View {

ZStack(alignment: .anchor) {

Image("rogue")

.alignmentGuide(HorizontalAlignment.anchor) { d in d[.trailing] }

.alignmentGuide(VerticalAlignment.anchor) { d in d[.bottom] }

Image("dragoon")

.alignmentGuide(VerticalAlignment.anchor) { d in d[.top] }

Image("brawler")

.alignmentGuide(HorizontalAlignment.anchor) { d in d[.leading] }

.alignmentGuide(VerticalAlignment.anchor) { d in d[.bottom] }

}

}

}

The process of alignment of a z-axis stack is much the same as a horizontal, except it maintains two alignment values, and compares both. Ordinarily this results in the single same point on each view being aligned over top of each other, but through custom alignments, we can achieve custom layouts:

Alignment Across Views

The examples thus far have shown alignment within a single stack view, but for more complicated layouts, we frequently use a nested hierarchy or multiple stacks. How do we align views using custom alignments through such?

Fortunately after layout of a stack is complete, the stack itself now has a value for our custom alignment guide, the value is simply that it used for aligning its children.

This means that the HStack views in our .feet example can be placed

inside any stack that is also aligned by .feet.

To illustrate we can just look at the code used to add the yellow line

in the sample previews in this post. The HStack in the examples was

contained within a ZStack, along with a 1px high Rectangle.

The ZStack was then aligned using a vertical alignment of .feet,

resulting in the two views being aligned together correctly.

struct ContentView : View {

var body: some View {

ZStack(alignment: Alignment(horizontal: .center, vertical: .feet)) {

HStack(alignment: .feet) {

Image("rogue")

.border(Color.red)

.alignmentGuide(.feet) { _ in 61 }

Image("dragoon"

.border(Color.red)

.alignmentGuide(.feet) { _ in 84 }

Image("brawler")

.border(Color.red)

.alignmentGuide(.feet) { _ in 70 }

}

.border(Color.green)

Rectangle()

.fill(Color.yellow)

.frame(width: 200, height: 1)

}

}

}

Note that the Rectangle for the line doesn’t specify a value for the

.feet alignment guide, so the default from the alignment definition

will be used—in this case, .bottom.