A secondary view, be it background or overlay, can be any view. We know from flexible frames that we can create views of fixed sizes, sizes based on their children, or sizes based on their parent. And we saw above that the proposed size of a secondary view is the fixed size of a parent.

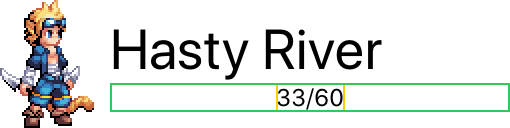

So let’s put all this together, and build something cool! A hit points bar for our character that shows how much damage they’ve taken.

We ideally want the size of the hit points bar to be flexible to our needs, as we’ll use it in a few different places. For the character list, something like the following code is our goal:

struct ContentView : View {

var body: some View {

HStack {

Image("rogue")

VStack(alignment: .leading) {

Text("Hasty River")

.font(.title)

HitPointBar(hitPoints: 60, damageTaken: 27)

.font(.caption)

.frame(width: 200)

}

}

}

}

Getting Started

Our ideal code has the vertical size of the hit point bar being determined by a font size, and the horizontal size being as wide as possible, while allowing a frame to constrain it.

Since the size of the font is key, we’ll start by having a Text view

with a label saying how many hit points the character has left:

struct HitPointBar : View {

var hitPoints: Int

var damageTaken: Int

var body: some View {

Text("\(hitPoints-damageTaken)/\(hitPoints)")

.border(Color.yellow)

}

}

That’s actually already enough to get started. Contrary to my usual

examples I’ve explicitly added a yellow border to the text so that we

can see what’s happening. We’ll also add a green border to the point we

use the HotPointBar:

HitPointBar(hitPoints: 60, damageTaken: 27)

.font(.caption)

.frame(width: 200)

.border(Color.green)

I recommend using modifiers like .border and .background to debug

your custom views, they can be hugely insightful.

The Text has no font size specified of its own, so will inherit it

from the environment, meaning the .font applied to the HitPointBar

itself will be used.

As we saw in flexible

frames HitPointBar is

a layout-neutral view, so will tightly wrap the Text within it; and

since we didn’t specify a height for the .frame, the frame is

layout-neutral in height as well.

Thus the height of the HitPointBar is exactly the height of the text

in the given font size, which is exactly what we want.

The width though is not yet correct, since the Text only has the width

necessary for its contents, and HitPointBar tightly wraps that, it’s

only the .frame in the parent that is the full width, and that’s in

the wrong place to be useful.

We still need the HitPointBar itself to fill this frame.

In flexible frames I introduced infinite frames as frames that fill their parent, so we can use one of those (and drop the border from the parent call site):

struct HitPointBar : View {

var hitPoints: Int

var damageTaken: Int

var body: some View {

Text("\(hitPoints-damageTaken)/\(hitPoints)")

.frame(minWidth: 0, maxWidth: .infinity)

.border(Color.green)

}

}

We make the frame of the text have the size of the parent in width

(which we then fix in the ContentView), while still allow it to be

layout neutral in height.

The result looks the same:

But this time I’m able to place the .border around the .frame inside

the HitPointBar. The text is positioned within that frame, and this

frame can be the foundation of the rest of the view.

Once you learn to rely on the fixed sizes of views, and layout-neutral behavior of combinations of views, it’s actually easy to create flexible custom views by using the layout system rather than fighting it.

Okay so let’s add a secondary view to make the bar. Nothing says damage and hit points like a red lozenge:

struct HitPointBar : View {

var hitPoints: Int

var damageTaken: Int

var body: some View {

Text("\(hitPoints-damageTaken)/\(hitPoints)")

.frame(minWidth: 0, maxWidth: .infinity)

.foregroundColor(Color.white)

.background(Color.red)

.cornerRadius(8)

}

}

Pay attention to the ordering of things, and remember that .frame

creates a new view around the Text inside it. We deliberately attach

the .background secondary view to this frame, which is taking its

width from its parent and its height from its children views.

We then apply a .cornerRadius to the combination of the frame and

secondary view, which encases them both in a clipping view that masks

the boundaries. This means it’ll apply to the Text, background color,

and anything else we added.

We also set the foreground color of the Text to white for better

contrast.

Looking good, but we want that hit point bar to be filled with green if they’ve taken no damage, filled green from the left and red from the right according to how many hit points they have left.

That wouldn’t be too hard if the size of the view was fixed, but we’ve deliberately decided to make it flexible and up to the parent. Worse, we’ve decided that the height is going to be dictated by dynamic type, so is flexible as well.

There’s a tool for this, the geometry reader, and while it always expands to fill its entire parent, when we use it as a secondary view, the parent is the view it’s attached to.

For clarity I like to separate out complex secondary views into a separate view, so we first rewrite our control to do this:

struct HitPointBar : View {

var hitPoints: Int

var damageTaken: Int

var body: some View {

Text("\(hitPoints-damageTaken)/\(hitPoints)")

.frame(minWidth: 0, maxWidth: .infinity)

.foregroundColor(Color.white)

.background(HitPointBackground(hitPoints: hitPoints,

damageTaken: damageTaken))

.cornerRadius(8)

}

}

struct HitPointBackground : View {

var hitPoints: Int

var damageTaken: Int

var body: some View {

Color.red

}

}

Now we know we’re going to want two things in this geometry view, a green color from the left for the hit points remaining, and a red color from the right for the damage taken.

There’s a few different ways to achieve that, and they’re all equally valid. For this example we’ll have the red color fill the entire view, and place a green color in front of it, so we’re going to need a z-axis stack for that with a leading alignment.

This all then goes inside the GeometryReader:

struct HitPointBackground : View {

var hitPoints: Int

var damageTaken: Int

var body: some View {

GeometryReader { g in

ZStack(alignment: .leading) {

Rectangle()

.fill(Color.red)

Rectangle()

.fill(Color.green)

.frame(width: g.size.width

* CGFloat(self.hitPoints - self.damageTaken)

/ CGFloat(self.hitPoints))

}

}

}

}

In general terms this view looks like something you’ve almost certainly written before.

The GeometryReader expands to fill the proposed size given by the

parent, except this time that proposed size is the size of the frame we

put around the text, based on the text size.

A ZStack containing two views with leading alignment is nothing

special, the first is a Rectangle filled with red—switching from

just using the color for maximum readability, and the second is also a

Rectangle just filled with the green instead.

The second Rectangle is constrained in size by placing it inside a

frame, layout neutral in height, but fixed in width to that derived from

the percentage of hit points remaining and the width returned by the

GeometryReader.

The result is the flexible hit point bar we wanted: